Powerful but reclusive Turkish cleric – BBC’s interview with Fethullah Gulen

Date posted: September 11, 2016

Fethullah Gulen has been called Turkey’s second most powerful man. He is also a recluse, who lives in self-imposed exile in the US.

An apparent power struggle between his followers and those around the Turkish Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has reached a new pitch of intensity and loathing.

Since arriving in the US in the late 1990s, Mr Gulen, 74, has not given a single broadcast interview. What rare communication there has been with the media has almost exclusively been conducted via email.

But now, the BBC has had exclusive access to the Muslim cleric. I travelled with Guney Yildiz from the BBC Turkish Service to a remote part of Pennsylvania to meet the man.

In the interview, Mr Gulen denied using his influence to start investigations into alleged corruption among senior members of Mr Erdogan’s AK Party which have led to a number of police commissioners being sacked and to some of Mr Erdogan’s allies being arrested.

Frailty

Two moments stood out from my interview with Mr Gulen. Neither had anything to do with what he said.

The first occurred as our camerawoman, Maxine, was making some last-minute adjustments to the lighting. Mr Gulen waved his hand wanly, and a man rushed forward from the chairs arranged on one side of the room. In his haste, he stumbled over the carpet. He was Mr Gulen’s personal physician.

He took the blood pressure of his elderly charge, before poking, one-handed, a pill from its packet and giving it to his patient to chew. The testing and dispensing routine would be repeated later in the interview.

The second incident happened at the end of our long conversation, which was prolonged by the consecutive translation. Moments after Mr Gulen stood up, he swayed. One of his 13 followers in the room caught him by his shoulders, and righted him.

Fethullah Gulen may be, as the former US ambassador to Turkey James Jeffrey told me, Turkey’s second most powerful man – an Islamic cleric who sits atop a movement with perhaps millions of followers, worth perhaps billions, with a presence, often through its high-achieving schools, in 150 countries.

But Mr Gulen’s own physical capabilities appear to be ebbing. He has, we were told, a series of chronic ailments, and is recovering from an upper respiratory disorder. Indeed, just before the interview, one of his closest colleagues told me it had been on the cusp of being cancelled.

Sense of mystery

Mr Gulen had all along been deeply reluctant to agree to the interview request, but had been “persuaded” by his advisers.

And yet… even during the interview, the cleric proved surprisingly elusive. Surprising, because Mr Gulen has been almost universally depicted as being in a virtual death clinch with his erstwhile ally, Prime Minister Erdogan, in a struggle for power and vengeance in Turkey.

Whoever struck first, Mr Erdogan has recently been seeking to curb the reach of Mr Gulen’s Hizmet (“Service”) movement, whose followers – or “participants” as some of them prefer to call themselves – include police chiefs and prosecutors leading corruption investigations into the heart of government. Mr Erdogan has decried their work as that of “a state within a state”.

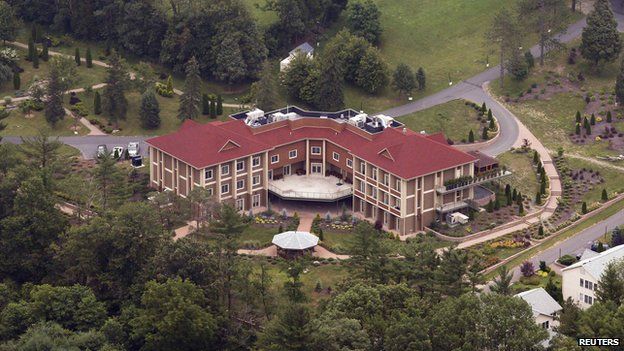

So why had Mr Gulen finally consented to allow the BBC to meet him on the extensive private estate in small-town Pennsylvania? (Mr Gulen came to the US after being charged with crimes against the state – charges he was later cleared of.)

The interview did not make his intentions altogether clear. But his advisers said the purpose was to clear up some misconceptions.

You can understand why when you read the adjectives that tend to hang around reports on Mr Gulen and Hizmet: “secretive” (Foreign Policy magazine); “shadowy” (The Economist); “opaque” (Los Angeles Times); “insidious” (Wikileaks cables).

And so, time was made before and after the interview to take us around the frozen grounds, which we were told were primarily a vacation retreat for families.

Image captionMr Gulen’s tiny bedroom – a surprise, given the size of his residence

Image captionMr Gulen’s study: From here he manages a big network of followers

Mr Gulen lives in a smaller building on this private estate in Pennsylvania Image copyright REUTERS

Modest rooms

Mr Gulen, we were shown, lives not in the large complex that is often depicted in photographs, but a smaller adjacent building. We were taken to see his office and minuscule bedroom with single bed.

Twelve of us, not including Mr Gulen, squeezed into his private space to look at his collection of sand from Turkish beaches, his dark wooden bookshelves, his low-slung single bed with a furry brown cushion at one end, his prayer mat and outsized Koran.

When we did eventually meet, he appeared a man in discomfort. Occasionally the smallest of smiles would play at the corners of his mouth.

More often, as he waited for one of his long answers to be translated, he would close his eyes, and tilt his soft, wide face back in his armchair, with a look not of repose but of pain. And whether by political design or medical exhaustion, he seemed keen not to stoke too directly his feud with the prime minister.

He preferred passive to active verbs, airy plurals rather than specific singulars: “I will remain personally silent, I will not return their acts.”

Image captionMr Gulen was also interviewed by the BBC Turkish Service

‘Phantom threat’

Of Hizmet’s alleged direct involvement in the corruption investigations, he said that some of the demoted, sacked or reassigned members of the police and judiciary “were not linked to us”.

“These moves were made to make our movement appear bigger than it already is and to frighten people about this non-existent phantom threat.”

Why, in that case, have so many people – academics, newspapers, diplomats without a dog in the fight – suggested that it is inconceivable that he, Mr Gulen, did not give the direct order for the net to close in on Mr Erdogan’s allies? Particularly after Mr Erdogan had moved to close down Hizmet schools in Turkey?

“It is not possible for these judges and prosecutors to receive orders from me. I have no relation with them. I don’t know even 0.1% of them.”

But also a tinge of sarcasm: “People in the judiciary and the police carried out investigations and launched this case, as their duties normally require. Apparently they weren’t informed of the fact that corruption and bribery have ceased to be criminal acts in Turkey.”

There was a time when there was a clear overlap in ambition between the apparently mild Islamic approach of this cleric, and the apparently mild Islamism of the AK Party under its coming man, then new prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

But were there not equally clear signs of divergence now, for example over Mr Erdogan’s embrace of peace talks with the armed Kurdish separatists, led by their jailed leader Abdullah Ocalan?

Kurdish tensions

Ocalan, said Mr Gulen, was “uneasy with what we were doing with the Kurdish people” (through the extension of Hizmet schools deep into Kurdish territory).

“They didn’t want our activities to prevent young people joining the militants in the mountains. Their politics is to keep enmity between Kurdish and Turkish people.”

The establishment of schools and investment in the region “were regarded as if they were against the peace process”.

What of the heightening of tensions between Turkey and Israel in recent years? “They try to portray us as a pro-Israeli movement, in the sense that we have a higher regard for them than our nation. We are accepting them as a people, as part of the people of the world.”

These quotations are culled and distilled from what others tell me is his peculiarly baroque language. One of his disciples explained that 15% of his speech is unlike anything normally heard in Turkish: Shakespearian rather than modern English, he said.

So given that, and given how I had seen – just in that room, and in the tortured process it had taken to set up the interview – the devotion shown by his followers, I asked a pointed question, seeking a direct answer. If you, Mr Gulen, were back in Turkey this year for the forthcoming local elections, and then presidential elections (in which Mr Erdogan is widely expected to run, in the hope of ruling with enhanced powers), who would you vote for?

Mr Gulen draws back, then hints; draws back again, hints again: “I don’t have the intention to say anything on that matter.

“If I were to say anything to people I may say people should vote for those who are respectful to democracy, rule of law, who get on well with people. Telling or encouraging people to vote for a party would be an insult to peoples’ intellect. Everybody very clearly sees what is going on.”

At one point, in the middle of his answer, he also comes up with the memorable circumlocution: “I haven’t even decided to say anything to that effect.”

And so that question which had hung as low as the clouds on that freezing day in the Poconos, Pennsylvania: Why, I asked several of his advisers-followers-participants, had Mr Gulen agreed to this interview? “To set the record straight,” they answered.

Straight, though, may not mean clear.

Source: BBC , January 27, 2014

Tags: Defamation of Hizmet | Fethullah Gulen | Hizmet (Gulen) movement | Hizmet and politics | Turkey |